James Booker

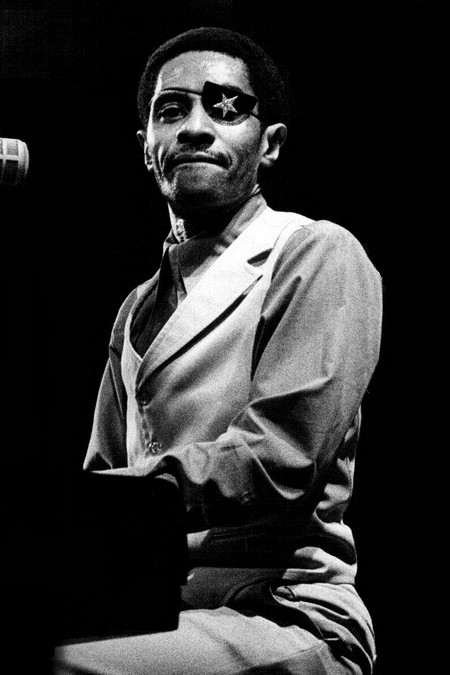

Piano legend James Booker stands out as a somewhat solitary but absolutely unique figure in the music history of New Orleans. Allen Toussaint and Dr. John have called him a genius. But his idiosyncrasies, lifestyle and drug habits impeded him from fully realizing his huge potential.

Bayou Maharajah

The Tragic Genius of James Booker is precisely the subtitle of Lily Keber’s portrait film from 2013, Bayou Maharajah, which has now been released as DVD. Bayou Maharajah was one of the nick names Booker earned. Another was Piano Prince of New Orleans. But he himself would at times find The Black Liberace closer to his flamboyant self. In an interview in 1977, on the highest level of success he had experienced in his career, he is heard acknowledging that he might cheat himself out of the artistic peak he saw preserved for him, thus demonstrating a presentiment of the tragic consequences of his self destructive behavior.

Keber provides insight in both the genius and the tragedy of a life otherwise surrounded by myth and incredible stories more than knowledge. Booker obviously had learned from the New Orleans piano tradition, not least Professor Longhair. However, whereas Longhair mostly created his groove by a syncopated right hand played against a simple left hand boogie bass line, Booker in his left hand alone combined rythmic elements from New Orleans jazz and r&b into a unique eight-to-the-bar groove with a strong bass line drive and chord progressions filled in. Moreover, his technique was far better, which allowed him to draw on and integrate a much wider variety of sources and styles, not least classical music, in his music. He was known for being able to create a meaningful medley out of any random selection of songs. On the other hand, Dr. John’s description of him as “the best black, gay, one-eyed junkie piano genius, New Orleans has ever produced” also sets the scene for some of his struggles.

Besides interviews with a wide range of persons who were close to Booker, the well researched film contains a lot of exciting footage, including some very touching moments from live performances. In an extremely interesting bonus, several prominent New Orleans pianists explain and demonstrate Booker’s piano style and technique.

Booker was known to be an intelligent and well read person with an extraordinary sensitivity. His personality always transpired in his performances. He made all songs into personal statements drawing on his biography and personal experiences – by changing the tempo, the accentuations, or by adding his own verses. His own lyrics are often hard to decipher, though, full of coded messages and insider jokes as they are. He could change tempo or dynamics within a wide range, from exuberant joyful, sometimes sarcastic, symphony to quiet slow and emotional torch song. His mood was visible in his gestures and audible in his voice. He loved to dress up in weird costumes and often wore a wig. He would joke or flirt with a guy in the audience while playing. He would engage in lengthy dialogues with the audience – or lecture or even scold it.

Early Years

James Carroll Booker III was son to a former dancer from Texas who converted to be a Baptist minister when he married. His mother was raised in Mississippi. The father played piano in the church and the mother sang in church choir. Booker was born 1939 in New Orleans, but because the father became ill he was early on moved to grow up by his mother’s sister in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi. In Booker’s own interpretation, Jelly Roll Morton died “around that time” (he died in 1941) and he also passed nearby Biloxi at some stage, implying that Jelly Roll’s spirit was transferred to Booker. Even though he claimed that his sister was much better than him, he was a child prodigy studying classical music.

Eight years old he moved back to his parents in Peniston St., New Orleans, where he started in school with the likes of Charles and Art Neville and Allen Toussaint. Nine years old, he was hit by an ambulance and dragged for some 30 feet. He broke his leg at eight places, which left him limping for the rest of his life. In the hospital they gave him morphine, according to himself thereby introducing him to the euphoria from drugs. The film clarifies that the song Papa Was a Rascal contains a hidden hint to this event. The song describes how he at the age of nine fell in love with a sweet rushin’ (sounds like Russian when sung) woman, and this ‘lady’ is a reference to heroin.

But of course, when a nine year old boy has sex with a Russian woman, Booker would jokingly have to add the warning that “we’d better watch out for the CIA”. Or maybe it wasn’t just a joke. Booker was notoriously tormented by paranoia and saw conspiracies everywhere around him.

However, there are more verses of this song, which the film unfortunately does not lay bare. Although the lyrics clearly not should be read literally, the two first verses of the song appear to refer to a temporary split up of his family. After all, the song is called Papa Was a Rascal. Firstly, some white woman seduced his father (in Booker’s description so provocatively that she made love to him in front of KKK); and secondly, his father moved to Boston and got involved with a mafia woman. At the very least, more conspiring is going on!

Booker moved back and forth between New Orleans and Bay St. Louis until 1953 when his father died and Booker was 14; from then on he lived permanently with his older sister Betty Jean and his mother in New Orleans. According to Allen Toussaint, his piano playing was fully deveoped, when he was 12 years old.

James Booker: “Papa Was a Rascal” (Booker) 1978

Early Career: Sideman Years

Betty Jean sang gospel on a radio station and Booker, aged 12-13, followed her and ended up playing piano in a jazz and blues show. At this time, he would also hang out with another talented youngster, Mac Rebennack (later to be known as Dr. John), outside Cosima Matassa’s J&M Recording Studio on Rampart Street. Eventually, in 1954, Dave Bartholomew would offer him to record “Doin’ the Hambone”/”Thinkin’ ‘Bout My Baby” as Little Booker on Imperial as the youngest ever to record on the label. The record did not sell well, but it earned him a reputation as musician and came to mark the start of a life as session and touring musician that would last the next twenty years. As a minor at first, his mother had to sign a paper declaring him emancipated.

Booker was able to immediately adapt himself to any style. Irma Thomas tells in the film that she before some gig explained what she wanted to sing. Booker said “OK” and that was the rehearsal. His technique even impressed Arthur Rubinstein, who played in New Orleans in 1958. “I could never play like that”, he said, “never at that tempo”.

The list of people he worked with through all these years is extremely long. Among the local stars were Fats Domino, Huey “Piano” Smith, Smiley Lewis, Mac Rebennack/Dr. John, Lloyd Price, Earl King, Snooks Eaglin, Shirley & Lee and Allen Toussaint. The nationally known stars included Little Richard, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Freddie King, T-Bone Walker, Dizzy Gillespie, Ringo Starr, Jerry Garcia, John Mayall, the Doobie Brothers and Geoff and Maria Muldaur.

As a sideman, Booker was seldom given opportunity to feature his unique talent. A few interesting examples are collected in the box below, which after all shows some of the diversity of contexts he could adapt to. Later, he would transform songs he heard and liked into his own personal interpretations.

James Booker Top 5 Sideman Appearences

- Fats Domino: “I’m Ready”, Fats Is Back (1968) Booker played on Fats Domino’s comeback album for Reprise, Fats is Back. Keith Richard called “I’m Ready” “one of the best rock & roll songs ever made” when he played it at The New Orleans Concert in 2004. Fats had recorded it earlier for Imperial, but this is the arrangement Keith re-used. Beautiful groove and solos by Booker

- Freddie King: “Sweet Thing”, Freddie King Is a Blues Master (1969) Freddie King was one of the great blues guitarists of the 1960s. Eric Clapton, for one, has learned a lot from him. Booker adds some typical rolls inside his chords within the blues groove.

- Ringo Starr: “Have You Seen My Baby”, Ringo (1973) Ringo recorded his first solo album in LA in 1973 – the time and likely place of the notorious eye incident. Booker played on this number, again with typical rolls and a half chorus solo.

- Aretha Franklin: “So Swell When You’re Well”, Hey Now Hey (The Other Side of the Sky) (1973) Booker wrote the song, but he gave it to Aretha Franklin and was not credited for it. Fats Domino also recorded the song on the above mentioned Fats is Back. Booker worked with Aretha, but here the piano playing is credited to Aretha herself.

- Maria Muldaur: “Lying Song”, Sweet Harmony (1976) Maria Muldaur looks and sings very much like a Southern States lady. But actually, she grew up in Greenwich Village in New York and started her career as part of the folk scene there back in the early 1960s. However, she has recorded with musicians from New Orleans many times. Booker’s rolls wonderfully fill out the slow tempo.

He did not record much in his own name during these years, though. Cosima Matassa describes him as a neither very self centered nor ambitious person.

In 1956 he made a single (“Heavenly Angel”/”You’re Near Me”) for Chess, but it did not have any success. Later, Johnny Vincent actually signed him for a three year contract with Ace Records. The single “Open the Door”/”Teenage Rock” was released in 1958, but when Booker discovered that Vincent had made Joe Tex overdub the vocal on the A-side, he was so disappointed that he backed out of the contract on the ground that he was minor. In 1960, he recorded the Hammond organ driven instrumentals “Gonzo”/”Cool Turkey” on the small Peacock label. The name “Gonzo” was taken from the scary drug dealer in the film The Pusher (1956). The reference to drugs, which is also apparent in B-side title and the later single “Smacksie” indicates that Booker’s misuse was fully developed at this time. He was also a lifelong alcoholic.

Surprisingly, “Gonzo” became a hit. Hunter S. Thompson was a huge fan of the tune and used the name “Gonzo” for his new journalism. Unfortunately, Booker had signed himself away from the composer credits. And three more singles of Hammond organ instrumentals on Peacock, “Smacksie”/”Kinda Happy” (1961), “Tubby Part 1 & Part 2” (1962?) and “Cross My Heart”/”Big Nick” (1962?), couldn’t repeat the success.

In 1967, first Booker’s sister and then his mother died within a short time span, and he is said to have never fully recovered from this loss. It fueled his paranoia. He saw it as a result of a conspiracy and perceived threats against himself everywhere.

Time in Angola and LA

In 1970, Booker was arrested outside of the Dew Drop Inn in New Orleans and sentenced to two years prison in Angola, the notoriously dreadful Louisiana State Penitentiary. Booker worked in the library, taught some of the inmates to read, practiced piano and played in the prison band, which included Charles Neville, Chris Kenner and James Black. He managed to get out on parole after six months, but immediately violated the parole by going to Los Angeles.

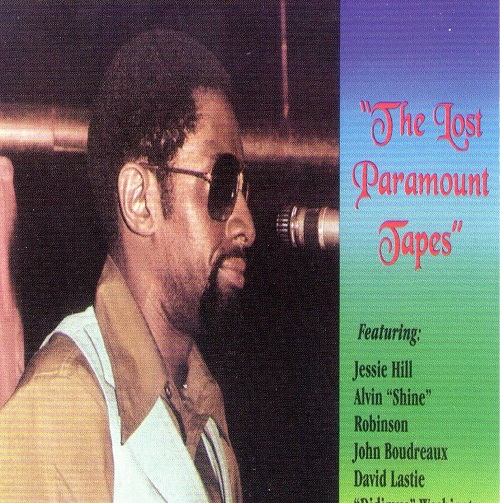

Booker’s unreliable behavior probably made record producers reluctant to sign him. But in 1973, after a methadone treatment, he got the opportunity to record at Paramount Studios with a lineup of musicians from New Orleans. However, Booker insisted on taking the master tapes with him to New York. No-one ever saw them again. In 1992 producer Daniel Moore found the early mix he made on the night of the recording and released it in 1995 as The Lost Paramount Tapes, twelve years after Booker’s death.

It was around 1973 Booker lost an eye. He launched many dramatic explanations of how it happened, but he wouldn’t let anyone know the truth. One story involved the mafia collecting drug debts, tying him to a chair and pulling his eye out. Another story involves a fight with a gang after a disagreement with a record company (possibly involving Ringo Starr). There were several other versions, some of which involved Jackie Kennedy or the CIA. A new branch grew from the consequence that he got a glass eye. He told that he had sold the glass eye for $ 1.500 to a tourist – sometimes identified as Ringo Starr. The star on his eye patch supposedly referred to Ringo.

Back in New Orleans, he was clean in periods but also more paranoid. A new recording session took place in the Sea-Saint Studios in 1975 with Cyril Neville, Earl King, Junior “Boy” Brown and Reggie Scanlan. Four numbers were recorded, the two of them after a break from which Booker and Cyril came back heavily loaded. One more time Booker insisted on bringing the master tapes with him, only to forget them in the taxi he left by. These recordings have only survived on a cassette copy that was made to Scanlan.

Peaking in Europe

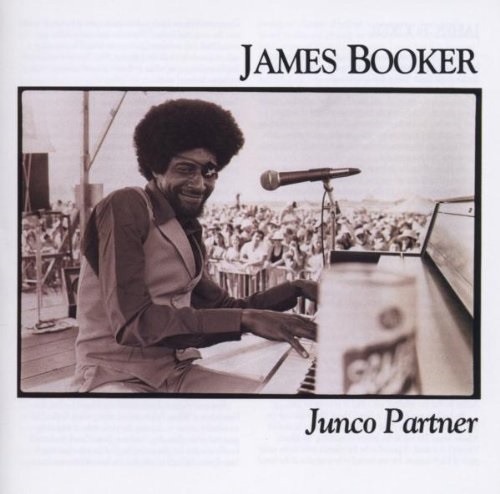

It was Booker’s performance at the 1975 New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival that got his career on the track. For one thing, he earned a recording contract with Island Records. Producer was Joe Boyd, who had recorded Booker as sideman in New York and who back then encouraged him to sing and play as a soloist. At the time Booker rejected that idea, but later he became convinced, probably because he needed money. However, it was a very natural idea, since Booker so clearly belongs to the tradition of making the piano sound like a whole band. A rythm group is only in the way. Booker had one condition for Boyd, though: that he brought a candelabrum to the session – to The Black Liberace. The recordings were made over two nights in the Sea-Saint Studios, and the result was released as Junco Partner.

Booker really found his right element on these recordings, the style and conception which unites his originals with the very personal cover versions. This included singing. His voice was not particularly great, and technically he was not a skilled singer. But he was, almost like Billie Holiday, able to phrase songs to give them a new meaning relating to his own life and experiences. To his disappointment, however, Junco Partner was first released in UK only.

For another thing, Booker attracted the attention of the German promoter Norbert Hess, who got him to Europe where he was touring several times during the years 1976-1978. Here Booker found an enthusiastic audience, and he was recorded live with a grand piano. The recordings from 29 and 30 October 1976 at Onkel Pös Carnegie Hall in Hamburg (released as The Piano Prince from New Orleans and Blues and Ragtime from New Orleans) counts as his best records. His performance at the Boogie Woogie and Ragtime Piano Contest in Zurich, Switzerland 27 November 1977 – released as New Orleans Piano Wizard: Live! – is equally good. It won him the Grand Prix du Disque de Jazz, which again earned him an invitation to play at the prestigious Montreux Jazz festival in 1978 – also released on record; unfortunately, this otherwise brilliant performance was marred by the addition of a heavy weight rhythm group on the last six out of ten tunes.

Several other live recordings from this period of variable quality are known, from various venues in England, France, Germany, Switzerland and Sweden, but also from New Orleans. A recording from Leipzig, GDR 1978 was released as Let’s Make a Better World in 1991 as the last LP produced in what was still GDR. I wonder what STASI made out of Booker. He was openly singing and talking about his drug use and alcoholism. He also identified a voice (from an official, a loudspeaker or the audience?) as being someone from the CIA, just as he explained certain other paranoid ideas of his. Clearly, this made the otherwise appreciative audience feel a little uneasy at times.

I shall post the complete Montreux performance, which is in quite good quality. But be warned about the rhythm group, presumably the backing group of Etta James and Cah McCall, which is added after 4 solo numbers. Booker was performing solo at the time; however, someone must have got the brilliant idea of adding this rhythm group. The group is presented before Booker arrives on the scene, but it does not show up until after a while, and Booker does not seem to be aware that it is meant to back him up. He accepts it, seemingly under the impression that he thereby is allowed to play more. Particularly the drummer Tony Cook is terrible. He has played with the funky James Brown, but he shows no understanding whatsoever of Booker’s subtle rhythms. Compare with John Boudreaux below. However, Booker does not get disturbed, he just plays his own thing and more or less ignores the rhythm group, leaving them to find out for themselves which songs he is playing and in which the keys.

James Booker: Live at Montreux Jazz festival 1978

Final Years

Back in New Orleans he didn’t find the same appreciation; he could hardly get a gig. His health was deteriorating, his body would tolerate alcohol less and less, and he lost the desire to travel. Every now and then he checked in at a psychiatric department – where he of course always entertained the doctors. John Parsons booked him for weekly gigs at the Maple Leaf Bar. The quality of the performances was at great variance. Parsons recorded him, though, throughout the whole period 1977-1982, and two collections of the best material released by Rounder in 1993 turned out very good, although the Maple Leaf piano isn’t exactly a grand piano: Resurrection of The Bayou Maharajah and Spiders on the Keys. The latter title refers to Booker’s own description of his style.

Throughout the same period, Booked was engaged by the Toulouse Theatre. He was supposed to create the right atmosphere for the public by hanging around and playing. He even got a room where he lived. There are bootleg recordings around from this engagement and from a lot of other New Orleans venues, but most of them suffer from poor sound and Booker in shaky form.

In 1982, Booker worked with a band at the Maple Leaf Bar, and in one of his better moments it was decided to record the band. The result, made in just four hours, was Classified, only Booker’s second studio LP released in his lifetime. It was reissued in an expanded version by Rounder in 2013. But although there are very good moments, it does not possess the same intensive focus as his best records.

Booker died in 1983, aged 43. Apparently, he got bad, and somebody drove him to the emergency room at New Orleans’ Charity Hospital – same hospital as he was born at. He died while waiting for medical attention. In an interview, Kleber claims that Booker’s death made such an impression on Dr. John that he manged to get off the hook.

James Booker Top 10

- “Gonzo” (Single 1960) Booker’s Hammond organ hit that made Hunter S. Thompson so high. It is oozing of 1960s.

- “Junco Partner” (The Lost Paramount Tapes 1973) New Orleanians John Boudreaux and “Didimus” Washington provide some of the most congenial drumming and percussion that Booker has ever been recorded with on this session. This is the reason I chose this version of the song over many other good recordings of it. Booker very oddly chose a small spinet tack piano instead of a grand piano to play on the sessions. But it swings anyway. “Junco Partner” was Booker’s theme song. It is a New Orleans classic, allowing everyone to add their own verses, a junkie anthem which used to be sung in Angola. Six months ain’t no sentence, it says, and the reason is that there are boys in Angola doing from one year to ninetynine, an explanation Booker could identify with. “Junco Partner” is credited to Shad and Brent and was first recorded by James Wayne in 1951. It is one of many songs based on “Junker’s Blues” by Willie Hall and first recorded by Champion Jack Dupree in 1940.

- “Goodnight Irene” (Junco Partner 1976) The famous song by Leadbelly. Booker identified with Leadbelly, because he too had been in Angola. Booker quotes from “Junco Partner” when he explains this in the intro. The story is that Leadbelly, who was sentenced for murder, got pardoned by the governor because of this song, but it is probably not true; however, he was pardoned. He may have picked up the song as early as 1908, but he clearly made it his own. It was first recorded in 1933 by Alan Lomax for the Library of Congress while Leadbelly still was in Angola. Booker very effectively combines a bassline and a funky two chord figure in his left hand, which he developed for another song while playing with dr. John. It gives a pulse not unlike the guitar on Leadbelly’s own versions, with some details added. The solo starts with classical phrases, but turns into something more funky.

- “On the Sunny Side of the Street” (Junco Partner 1976) Booker playing stride. In the film, Harry Connick Jr. beautifully explains the details of Booker’s amazing technique on this tune. There are extra bass notes to push the tempo into a typical New Orleans drive, and some complicated glissandos and rolls within the chords in the right hand. Booker’s repertoire was often inspired by the people he had worked with, and the inspiration for playing this song may have come from his collaboration with Dizzy Gillespie.

- “Pixie” (Junco Partner 1976) A Booker original instrumental. This time, he only plays the bass line in left hand, everything else is played with right hand. It sounds like three hands. It is a bluesy theme with a classical Chopin-like touch, where the chords gets turned up and down. Nobody else plays like this.

- “Life” (The Piano Prince of New Orleans 1976) Booker makes a very personal interpretation of this song by Allen Toussaint. On some versions, he sings “the needle is in so bad” rather than “the bullet”. His full eight-to-the-bar left hand gives the song a much more earthy drive than Toussaint’s own elegant version. In the end of the solo, Booker demonstrates how he can turn those very long classical runs into something quite bluesy. Note the exalted “danke schön”s, this was Booker experiencing a peak of recognition.

- “Please Send Me Someone to Love” (The Piano Prince of New Orleans 1976) Another fine example of how Booker makes a song his own. First, it shows the gospel inspiration from his childhood. As Dr. John remarks, Booker turned all songs into church songs. Later the call from the lonely singer becomes a love song. The left hand gives a quiet pulse, with a slight crescendo in the B-pieces. Again a solo with one long bluesy run.

- “Classified” (The Piano Prince of New Orleans 1976) Booker claimed to have written this song in Angola. It seems to transmit the experience that people shouldn’t be judged on their appearance. Apparently, he accused dr. John of having copied him on his “Qualified”. Note, after the introduction, how the initial straight left hand turns into Booker’s typical rolling chords.

- “Tico Tico” (Blues & Ragtime from New Orleans 1976) This tune is a Brazilian choro written in 1917. It was made a hit by Carmen Miranda in the 1940s. I have no clue as to why Booker chose to play this tune. Maybe he liked the long fast phrases. It could also very well be that he was fascinated by the Carmen Miranda stage persona. Anyway, it fits Booker’s classical mood very well; he attemps a sort of samba rythm and the melody gets a typical Booker treatment with lots of variations.

- “Baby Won’t You Please Come Home” (Blues & Ragtime from New Orleans 1976) Still another fine example of a personal interpretation. This tune mostly gets an indifferent uptempo treatment by socalled traditional jazz bands. By slowing down the tempo and actually taking the words seriously, Booker turns the song into a torch song. Booker uses the slow tempo to fill in some beautiful extended harmonies in the chord progression. Again a solo with a very long line.

DVD

Lily Keber: Bayou Maharajah – The Tragic Genius of James Booker, Cadiz

Selected Discography

Junco Partner (Hannibal, 1976)

Classified (Demon, 1982)

The Lost Paramount Tapes (DJM, 1995)

More Than All The 45s (Night Train International, 1996)

The Piano Prince from New Orleans (Aves 1976)

Blues and Ragtime from New Orleans (Aves 1976)

New Orleans Piano Wizard: Live! (Rounder 1987)

Live at Montreux (Montreux Sounds 1997)

Gonzo. James Booker Live 1976 (Rock Beat 2014)

Resurrection of The Bayou Maharajah (Rounder 1993)

Spiders on the Keys (Rounder 1993)

Leave a Comment